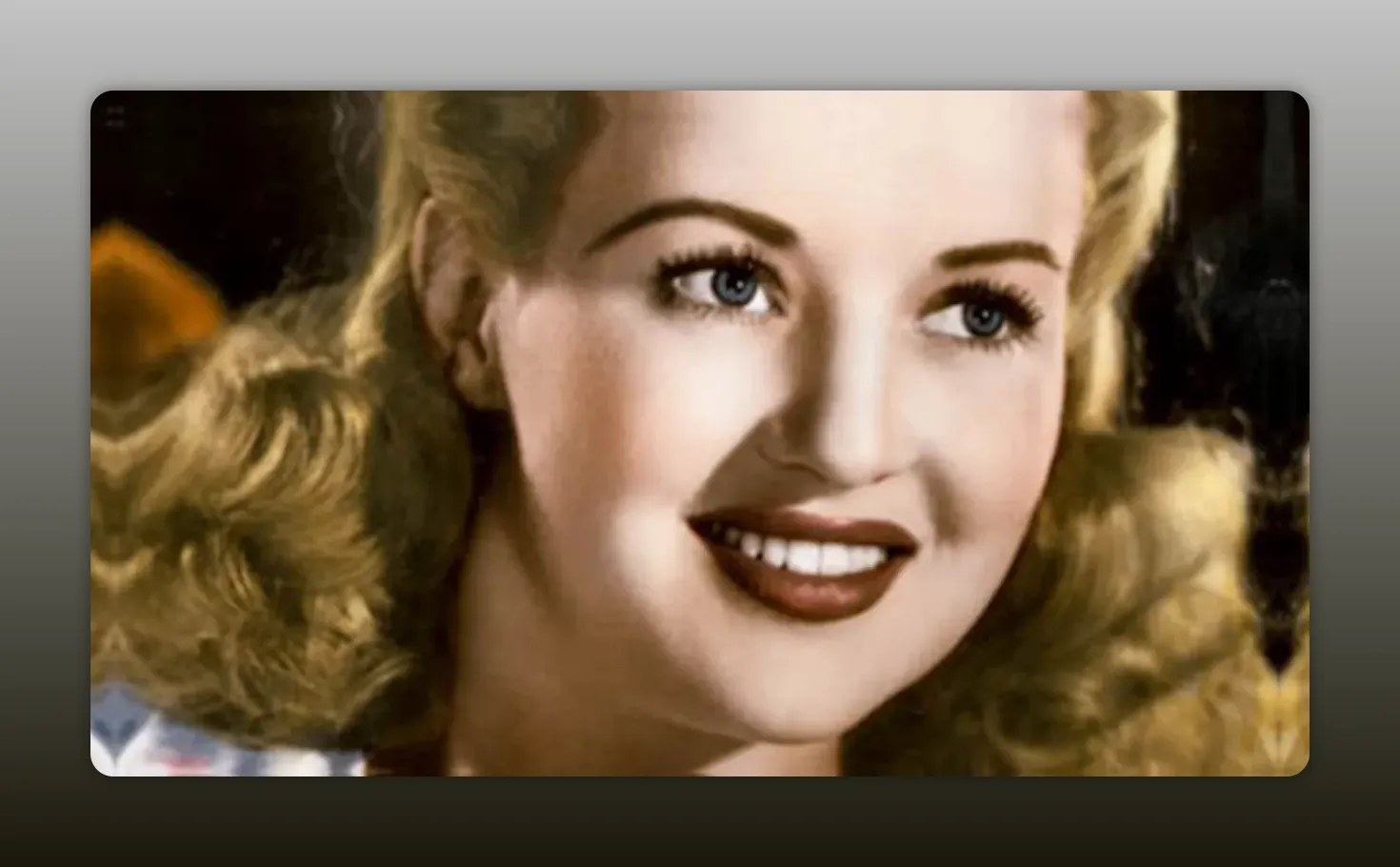

I have always been fascinated by Hollywood legends who were larger than life on screen yet human and vulnerable off it. Few stories capture that contrast better than Betty Grable’s. She was the epitome of midcentury glamour: a Technicolor queen, a dancer with perfect timing, the smiling pinup that lifted the spirits of millions of soldiers during World War II. At her peak she was the highest paid woman in America, an icon whose image was painted on aircraft and carried in the pockets of servicemen around the world.

This is the full, unvarnished story of Betty Grable. It is the rise of a small-town girl who became a national treasure, the cost of living under the old studio system, the painful private life behind a dazzling public image, and the quiet, sobering end that followed a life spent giving everything to show business. I want to walk you through her childhood, the shaping force of a determined mother, the slow grind of early films, the explosion of stardom in the 1940s, the changing tides of the 1950s, and the final chapters in Las Vegas stages, in love, and in illness. Along the way I will examine the cultural impact of her most famous pinup photo, the realities of the studio machine, and how Betty’s legacy still matters for performers and fans today.

From St. Louis to Hollywood: Childhood and Family

Betty Grable was born Elizabeth Ruth Grable on December 18, 1916, in St. Louis, Missouri. She was the youngest of three children in a household that combined several strands of European ancestry—Dutch, English, German, Swiss-German, and Irish. Her father worked as a stockbroker, while her mother, Lillian Rose, was a woman with a fierce belief that her daughter belonged on the stage.

Betty’s early life is often described in terms of opportunity, but it is more accurate to describe it as a life deliberately engineered toward stardom. Lillian enrolled Betty in dance and vocal lessons from the age of three. Clara Hoffman’s dance school in St. Louis was where the tiny girl first learned ballet and tap. Lillian did not simply encourage talent—she cultivated it. She entered Betty into local beauty pageants and musical contests, pushing her into situations designed to teach poise, presentation, and endurance.

There were costs. Betty won many contests and the local acclaim that follows, but she also developed anxieties that shadowed her adult life: a fear of crowds that made public appearances difficult and episodes of somnambulism, or sleepwalking, which friends later attributed to stress from relentless training and a childhood spent under intense scrutiny. These are not small details. They shaped the person behind the smile.

When Betty was 12, the family made a fateful trip to California. What began as a visit turned into a permanent move. Lillian decided Hollywood was where the future lay. The move also marked a break in the family: Lillian remained in California with Betty while her husband stayed behind. Whether that separation was born of practical necessity or of single-minded ambition, it changed the course of Betty’s life. Enrolled at the Hollywood Professional School, she trained with other young professionals and formed an early double act with Emlyn Peake, who would later be known as Mitzi Mayfair. This training environment sharpened young Betty’s craft and gave her the professional polish that would help when opportunity came knocking.

Learning the Trade: The 1930s and the Goldwyn Girls

Betty’s first steps into the film industry were small but notable. At age 12 she made an uncredited appearance as a chorus girl in Happy Days (1929). The system that governed Hollywood at the time was not kind to children and rules about age and contracts were strict. To circumvent this, Lillian and Betty would sometimes misrepresent her age to studios. It worked—until it did not. Once discovered, the deception could and did lead to Betty being dismissed from certain projects.

In 1930 Betty joined the Samuel Goldwyn troupe under the name Francis Dean as one of the original Goldwyn girls. That ensemble was a who’s who of future star power: Lucille Ball and Paulette Goddard were among that same group. Betty’s work in that period was physically demanding, repetitive, and often uncredited, but it taught her timing, stage presence, and how to hold herself under a camera’s unforgiving eye. These early lessons were crucial. The industry rewarded reliability and polish. Betty learned both.

By the early 1930s she was signed with RKO and adopted the stage name we still remember. She worked in small roles—Probation (1932), Cavalcade (1933), The Gay Divorce (1934)—each credit building a filmography that prepared her for larger parts. Studios in the 1930s treated performers like raw materials that could be shaped to studio needs; Betty was shaped continuously.

B-Movies, Broadway, and the Million Dollar Legs

The mid- to late-1930s were a mix of small-screen exposure and modest film roles. A loan-out to 20th Century Fox placed her in Pigskin Parade (1936) alongside a young Judy Garland. For a time Betty’s work was overshadowed by other rising names, yet her face and legs appeared more frequently on screen and in publicity. The nickname “Million Dollar Legs” began to become associated with her after Million Dollar Legs (1939), a B-movie that nevertheless left an outsized impression because of its promotional focus and Betty’s own physicality.

But the most significant shift in 1939 was not a film—it was theater. On Broadway she starred in Cole Porter’s musical Du Barry Was a Lady (1939), sharing the stage with Ethel Merman and Bert Lahr. Broadway success revitalized her career and put her firmly on the radar of 20th Century Fox executives, who were always looking for the next box office draw. That combination of stage success and screen experience set the stage for Betty’s explosive rise in the early 1940s.

The Reign of the Technicolor Queen: The 1940s

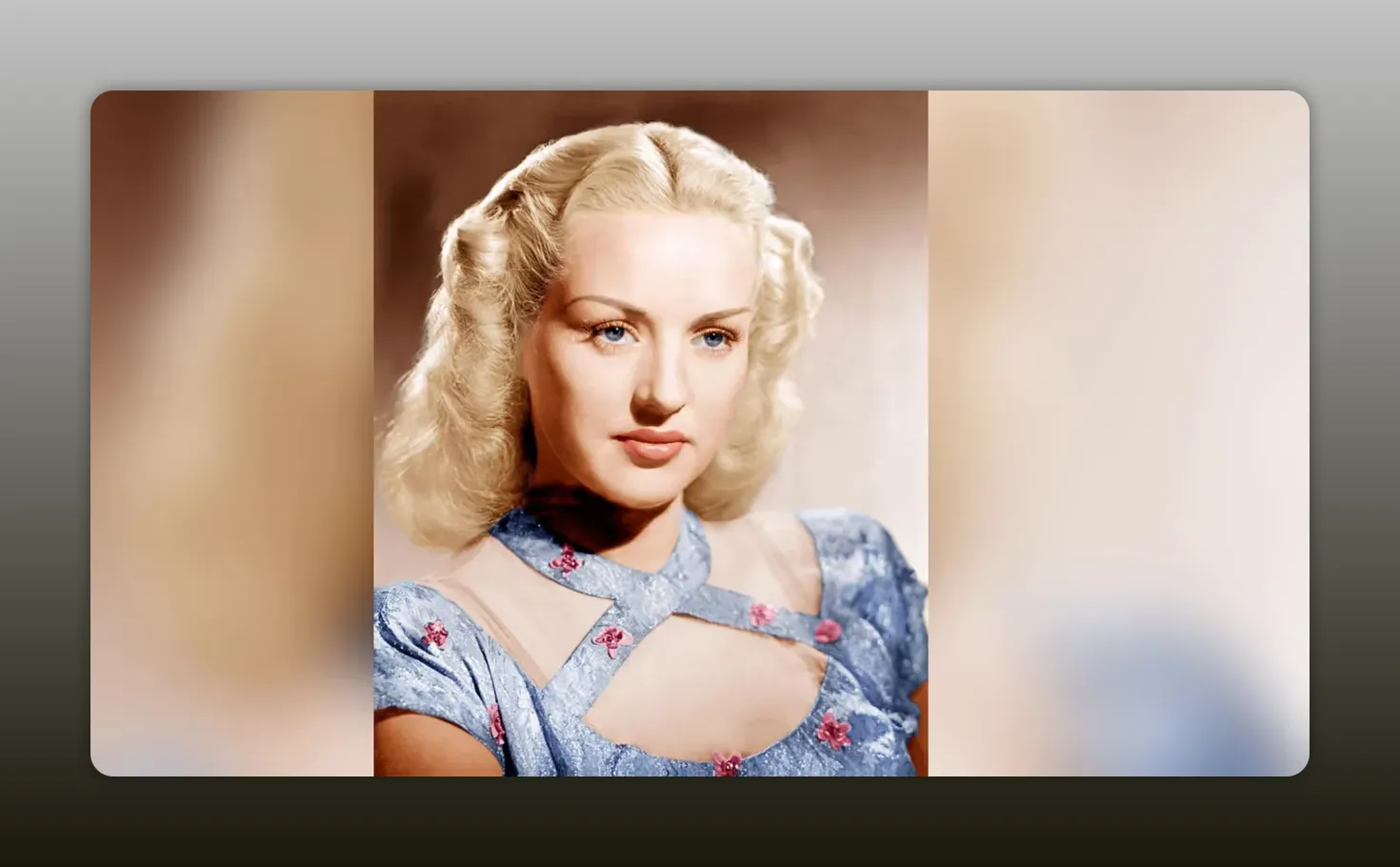

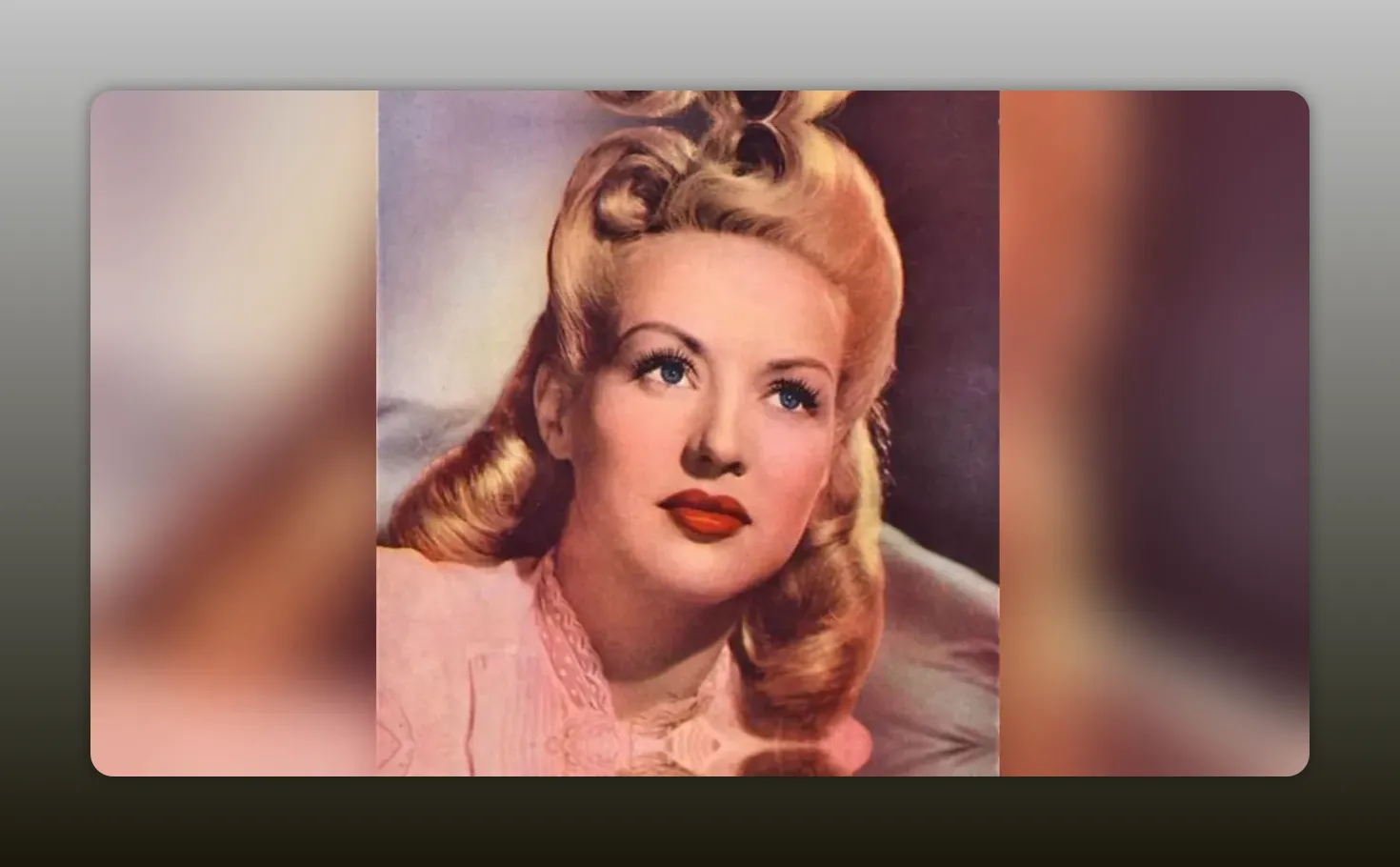

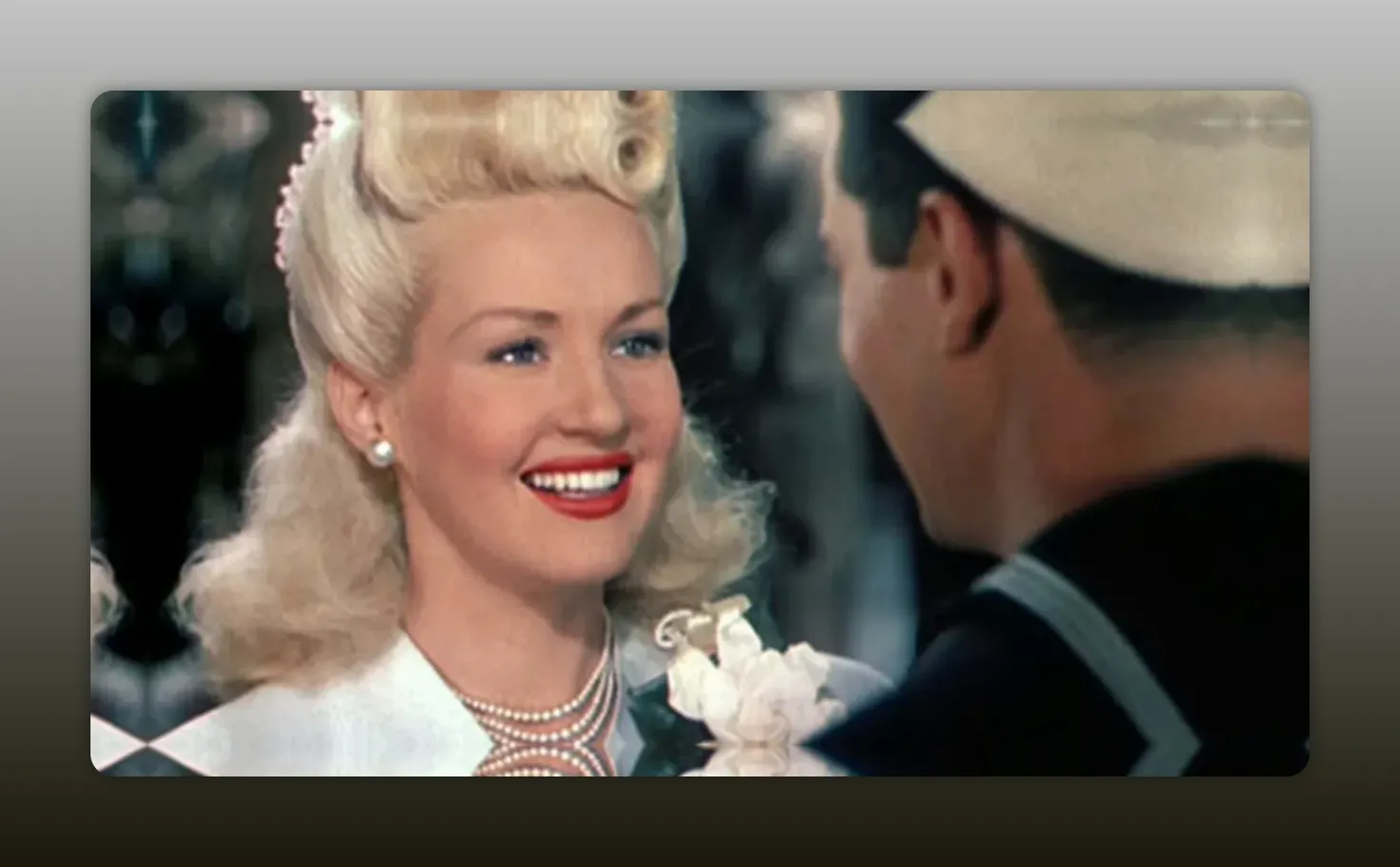

Betty Grable’s career truly took flight in 1940, beginning with Down Argentine Way. She replaced Alice Faye and immediately showcased the qualities that would make her a star: a radiant charm, impeccable dance technique, and an affability that translated beautifully to Technicolor. Her voice, her smile, and that perfectly photographed leg pose made her a natural fit for musicals built to lift spirits.

Over the next decade Betty became synonymous with big, bright studio musicals. Moon Over Miami, Springtime in the Rockies, Sweet Rosie O'Grady, Pin Up Girl—these were not merely films; they were cultural events. They were tailored to Betty’s strengths: buoyant song-and-dance numbers, screwball banter, and that wholesome allure that made her feel accessible and aspirational at the same time. Audiences loved her. Between 1942 and 1951 she was the highest-grossing female movie star year after year. In 1942 she was earning $300,000 a year, and she was regularly listed among the top ten most popular stars in Hollywood.

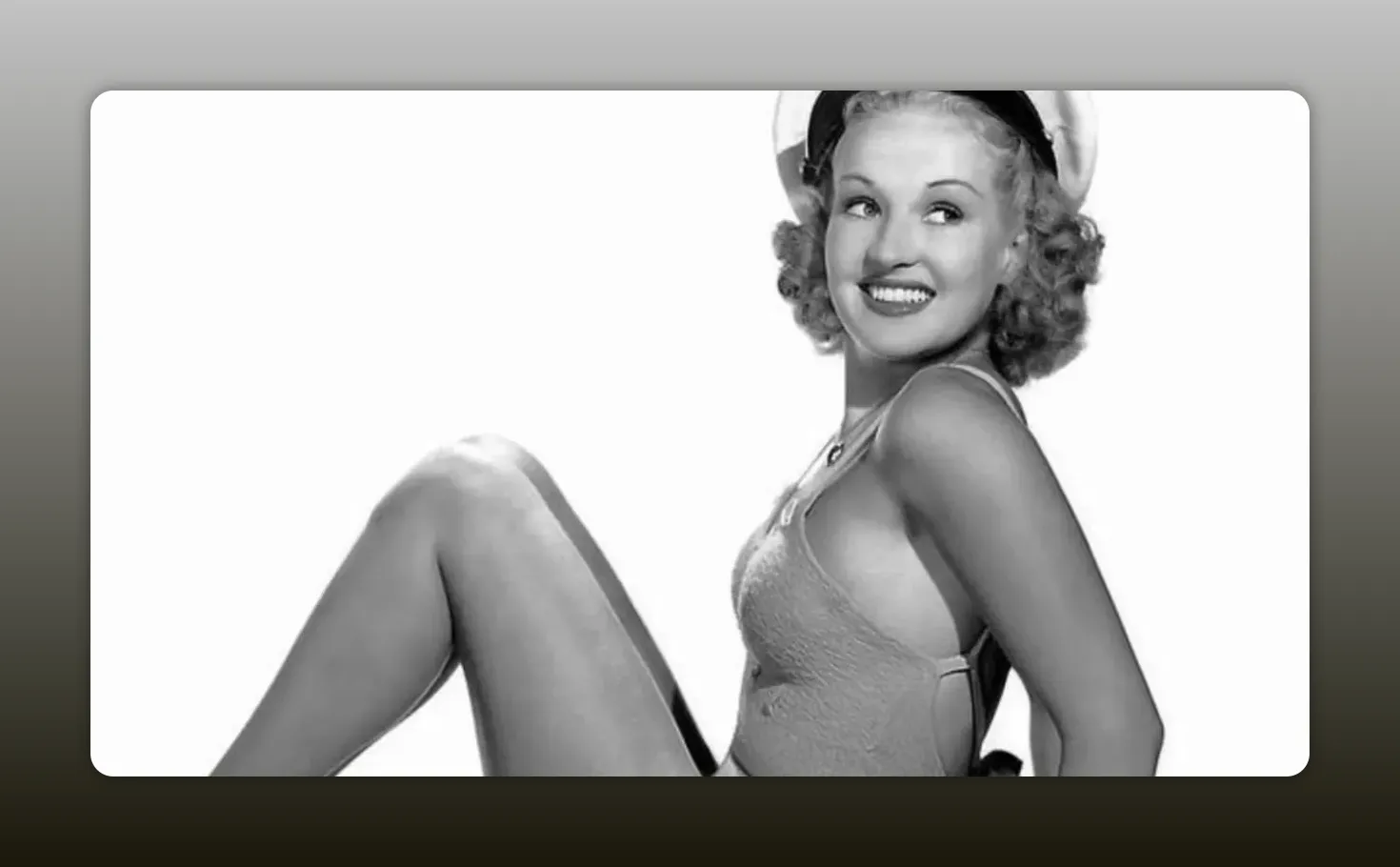

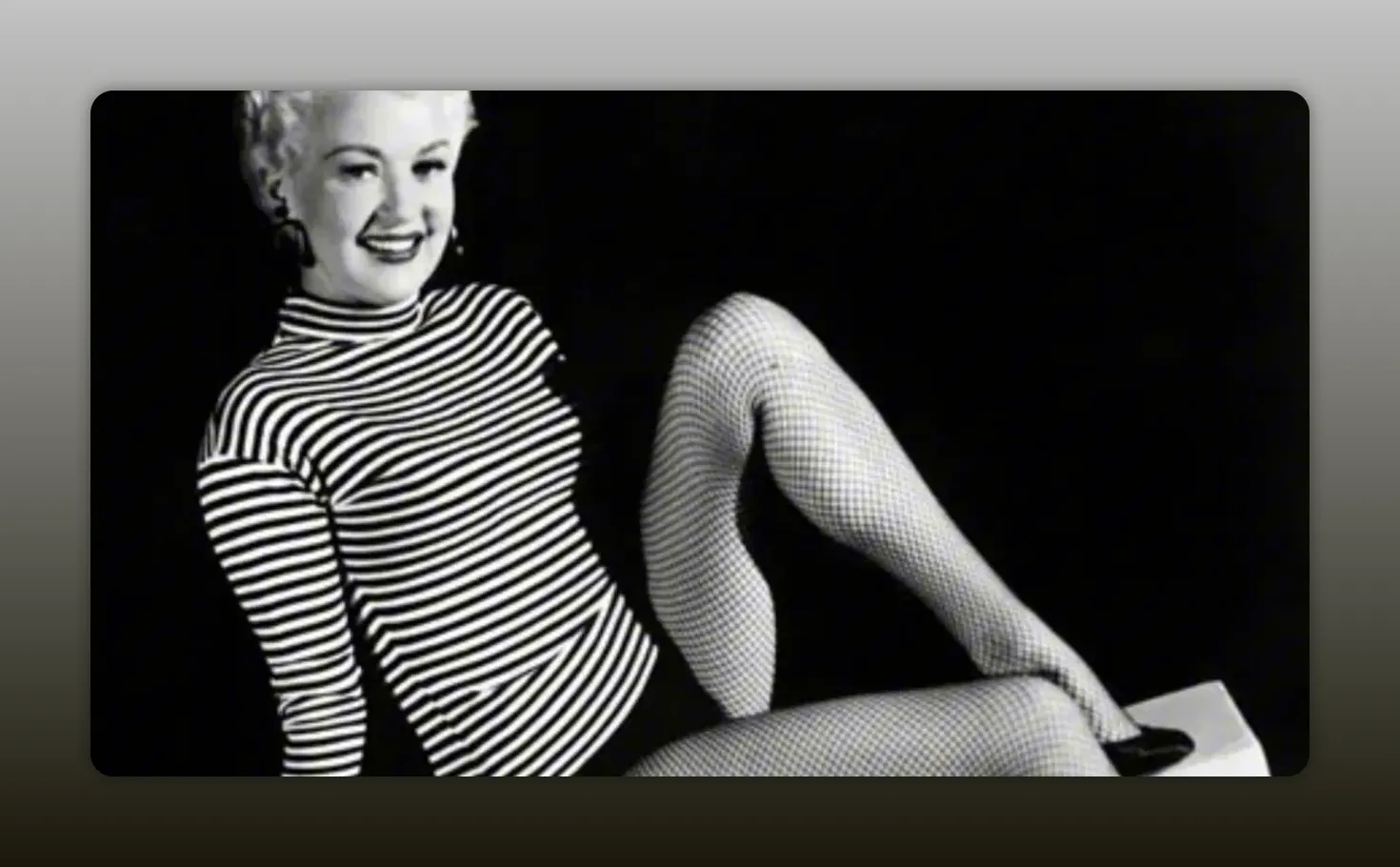

It is difficult to overstate how important Betty’s image became during the war. The wartime economy, the draft, and the realities of overseas service created a demand for symbols of home and hope. In 1943 photographer Frank Powolny captured an image of Betty in a white swimsuit, looking back over her shoulder with a playful smile and one leg bent. That photograph became the single most famous pinup of World War II. More than five million copies of it were distributed to American servicemen. They carried it, stared at it, and painted it on aircraft nose art. To troops in far-flung places the photograph represented an idea of America worth fighting for: wholesome, cheerful, and resilient.

Publicity surrounding the pinup cemented Betty’s status beyond box office numbers. She embodied an era’s aesthetic and mood. Her image was optimism made photographic. Her appeal was not raw sexuality; it was optimism and accessible glamour, a reminder of home and simpler pleasures in a violent, uncertain world. That is why the photograph’s power endured: it was not merely beauty. It was meaning.

Star Vehicles and Box Office Dominance

Studios designed films around Betty. Mother Wore Tights (1947) and When My Baby Smiles at Me are examples of movies that relied on her dependable star power. They were commercial machines: colorful, musically rich, and emotionally tidy. These films gave audiences what they wanted, and producers rewarded Betty with top billing, higher salaries, and dramatic national recognition. The studio system, at its best for an actress like Betty, could create a secure, lucrative career out of predictability.

There was a public stunt that has become part of her mythology: Betty insured her legs for one million dollars. Whether literal in all its legalistic detail or partly publicity bravado, the story underscores how much her image was tied to that specific part of her persona. Her legs were not merely a physical attribute; they were a brand.

The Shift in Hollywood: The 1950s and Changing Tastes

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw seismic shifts in American entertainment. The aesthetic of the musical and the screwball romantic comedy began to feel like relics to an audience increasingly exposed to film noir, method acting, and grittier subject matter. The rise of television changed consumption habits: movie theaters had to compete with free programming in the living room, pushing studios to find new ways to draw audiences back to cinemas. Audiences wanted more realism, more edge, and different kinds of actresses.

Enter Marilyn Monroe. Where Betty was sunshine, Marilyn represented a new, more overt glamour: sensual, ambiguous, and ripe for studio reinvention. Fox, always alert to trends and profits, shifted resources toward Monroe. The studio machine began cultivating a new blonde starlet who could carry box office the way Betty once had. This was not an instantaneous betrayal. It was a business decision driven by public appetite and changing style. For Betty, though, it meant a dislocation. She was no longer the studio’s undisputed queen.

The 1953 film How to Marry a Millionaire placed Betty in a rare ensemble with Marilyn Monroe and Lauren Bacall. Box office success notwithstanding, the film signaled the changing of the guard. Monroe’s presence pulled critical and popular attention in new directions. Although Betty retained top billing in promotional materials, public perception and studio favor had shifted. Around this time Betty made a consequential decision: she chose not to renew her contract with 20th Century Fox.

Refusing the Loan-Out and the End of a Studio Reign

Under the old studio system, stars were commodities owned by the studios that had signed their contracts. Actors could be loaned to other studios, cast in unsuitable roles, or forced into publicity farcicalities without meaningful consent. Betty resisted this. She refused to be loaned to Columbia Pictures for The Pleasure Is All Mine, a move that resulted in a temporary suspension from Fox. That suspension, emblematic of the clash between an artist’s desire for agency and an industry that prioritized obedience, damaged her relationship with studio executives.

Not renewing her Fox contract was an act of independence—but independence came at a price. The studios were both gatekeepers and providers. Leaving Fox meant losing steady, well-promoted film work and the kind of distribution muscle that turned a film into a national event. Betty hoped to reclaim a career on stage, or to find more interesting roles, but the market had changed. Broadway was fiercely competitive; the roles that might have fit her were often given to younger performers or those with a different sensibility. Without a studio’s infrastructure, her film offers dwindled.

Late Films, Touring, and the Vegas Years

Betty did return intermittently to film after leaving Fox. Meet Me After the Show (1951) and The Farmer Takes a Wife (1953) proved she still had audience appeal. But the films that followed increasingly lacked the national resonance of her wartime hits. Her final major film-era role in How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955) was an attempt to rekindle her comedically apt persona. The movie underperformed and the industry’s appetite for the old Technicolor maelstrom had waned.

As film roles became scarcer, Betty pivoted to live performance. Las Vegas was emerging as a home for aging and reinvented stars; the city’s nightclub scene offered performers direct access to fans and a steady paycheck. In that setting Betty could sing, dance, and connect without the control of studio publicity departments. She developed a cabaret act, performed in casinos, and reintroduced herself to audiences willing to see her beyond the silver screen.

Television variety shows in the 1960s also provided visibility. Guest spots on programs like The Jack Benny Show and The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour allowed Betty to display her comedic timing and remind audiences of her charisma. Live theater remained an important outlet as well: in 1962 she played Miss Adelaide in a Las Vegas production of Guys and Dolls, and in 1967 she toured in Hello Dolly, drawing ticket buyers eager for a familiar, comforting star. Each of these choices reflected a pragmatic and artistic recalibration: Betty was adapting to a new market, keeping her craft alive, and doing the work that sustained her financially and emotionally.

Performing into the Seventies

Betty’s stage work continued into the early 1970s. In 1973 she took on the role of Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday at the Alhambra Theatre in Jacksonville, Florida. It was a fitting capstone role—Billie is a character who seems light and loopy yet demonstrates wit and surprising depth. The choice suggested Betty was still interested in roles that allowed nuance and charm rather than spectacle alone.

Privacy, Pressure, and the Studio System

To understand Betty’s life is to understand the studio system that made and constrained her. For much of her career she existed inside a carefully managed persona. 20th Century Fox oversaw wardrobe, coiffure, romantic image, and public behaviors—everything a studio thought contributed to box office reliability. This arrangement had advantages: financial security, national fame, and steady work. It also had costs: limited creative freedom, personal intrusion, and a long-term pressure to remain marketable by ever-shifting standards.

Betty’s refusal to be loaned out to another studio is one of the clearest episodes in which those pressures came to a head. That moment reveals both her desire for artistic agency and the reality of what resistance could cost. The temporary suspension and the ensuing erosion of her relationship with Fox accelerated a career realignment that would define her later years. Her story is instructive to anyone studying how systems of production shape—even dictate—the arc of a performer’s life.

Marriage, Heartbreak, and Personal Life

Public adoration does not inoculate a person from private pain. Betty’s personal life was marked by two marriages and a long-term partnership that, together, tell a story of love, endurance, tolerance, and eventual peace.

Her first marriage, to Jackie Coogan, is often overlooked in favor of the later, more public union with bandleader Harry James. Jackie Coogan had been a child star remembered for his role in Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid. By the time he and Betty married in 1937 Coogan was entangled in a legal battle over mismanaged childhood earnings and faced financial insecurity. Their marriage lasted only two years. The mismatch in fortunes and the strains of public life made divorce inevitable. Betty later described the marriage as a lesson rather than a tragedy, an experience that taught her boundaries and self-preservation.

Harry James: A Complicated Partnership

Betty’s marriage to Harry James in 1943 was Hollywood’s fairy-tale-facing reality. The couple had two daughters, Victoria and Jessica, and for a significant stretch of time they presented an image of family stability. But Harry’s private struggles complicated that facade. He battled alcohol and gambling, and rumors of infidelity dogged him throughout their marriage. These issues strained the family dynamic. Some accounts suggest Betty turned to drinking at times to cope with the marital stress, though she rarely publicly criticized her husband.

The marriage lasted more than two decades—longer than many in their circle—yet by the early 1960s it had disintegrated. Financial disputes, drinking, and infidelity made restoration impossible. In 1965 the divorce was finalized. Betty handled the separation with remarkable restraint, maintaining dignity and prioritizing her daughters’ well-being over tabloid conflict.

Later Love: Bob Remick and Quiet Companionship

Following the divorce, Betty’s life quieted. She retreated from the most intense flashes of the spotlight and sought stability. That stability came in the person of Bob Remick, a dancer significantly younger than Betty. Their relationship was discreet and, by most accounts, peaceful. They never married, but they shared companionship and a measure of security that had been absent during her turbulent years with Harry. Bob accompanied Betty to Las Vegas shows and stood by her in her final illness. Their bond underlines an important truth about later-life relationships: they can be less about spectacle and more about emotional sustenance.

Health, Decline, and Final Months

By the early 1970s Betty’s health had begun to fail. Years of cigarette smoking—a habit that had been normalized in Hollywood circles of her era—caught up to her. In 1972 she was diagnosed with lung cancer. The diagnosis came late and the disease was already advanced. This period highlights an unforgiving reality: fame and salary do not always equal access to comprehensive healthcare, especially for actresses whose earnings decline as they age. Despite having been one of the highest paid women in America during her prime, Betty faced mounting medical bills and limited insurance coverage.

She continued to work for as long as she could, performing when possible to help pay for medical costs and to remain active. But by mid-1973 her condition had worsened and she was frequently hospitalized at St. John’s Hospital in Los Angeles. Friends and her longtime companion Bob Remick stayed close. By July 2, 1973, Betty Grable had passed away at the age of 56. The world lost an icon who had once defined an era of American entertainment.

Her funeral was small by modern celebrity standards but full of genuine affection. Colleagues from Hollywood’s golden age, friends, and family gathered to remember a woman who had given so much to her craft. Her ashes were interred at Englewood Park Cemetery in Los Angeles, a quiet place among other entertainment greats.

Legacy: Why Betty Grable Still Matters

Betty Grable’s life is often reduced to the famous swimsuit photograph or the million-dollar-legs anecdote, but her legacy goes deeper. Her career offers a clear case study of how the studio system could both create and constrain. She was given roles that maximized her strengths and built a bankable persona, yet she was also boxed into an image that limited the kinds of roles she could accept without risking studio reprisal. When she tried to exert agency, the consequences were real. That tension between commercial formula and personal aspiration is one of the enduring themes of Hollywood history.

Her status as the most famous pinup of World War II matters not because of a single picture but because the photograph became a symbol. It contributed to morale and represented how popular culture can become a psychological tool during times of national stress. Betty’s image connected directly to concepts of home, idealized femininity, and cultural continuity. That is why her legacy is often discussed not only in film history but in military history, fashion, and cultural studies.

Finally, Betty’s career arc is one of resilience and adaptation. After leaving the apex of film stardom she reinvented herself on stage and in nightclubs, and she continued to work in television and touring productions. Her ability to perform in front of a live audience—something many film stars find difficult after years in controlled studio environments—demonstrates a kind of craft that is enduring and human.

Lessons from Betty’s Life

- Talent and Ambition Can Be Engineered. Betty’s rise was the product of disciplined training, relentless promotion, and a mother who saw the stage as destiny. That combination propelled her but also created personal pressure.

- Success Is Contextual. Her image and style matched the tastes of the World War II era. When cultural preferences shifted, she—like many stars—found it difficult to maintain the same level of prominence.

- The Studio System Both Built and Boxed In. The studio system guaranteed work and fame but limited creative choice. Betty’s suspension for refusing a loan-out exemplifies that control.

- Public Image and Private Reality Often Diverge. The cheerful icon on posters did not mirror the complexity of her family life, drinking struggles around her marriage, or later health problems.

- Legacy Is Multi-Faceted. Betty remains a cultural figure for film history, wartime iconography, performance craft, and the evolution of celebrity culture.

Selected Film Highlights and Stage Work

For those new to Betty’s filmography, a curated list of significant works helps map the arc of her career:

- Happy Days (1929) — Early chorus girl appearance. Uncredited but important as an initial screen experience.

- Whoopee! (1930) — Goldwyn girls ensemble work. Uncredited musical numbers that taught her film rhythm.

- Probation (1932) — One of her earliest credited roles at RKO.

- Million Dollar Legs (1939) — B-movie that helped cement the 'legs' association.

- Du Barry Was a Lady (Broadway, 1939) — A crucial stage success that revived her career.

- Down Argentine Way (1940) — The film that started her run as a top 20th Century Fox star.

- Moon Over Miami; Springtime in the Rockies; Sweet Rosie O'Grady; Pin Up Girl — Representative Technicolor musicals of the 1940s.

- Mother Wore Tights (1947) — One of her most popular postwar successes.

- How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) — An ensemble film that symbolized a changing Hollywood.

- How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955) — Her last significant studio-era comedy.

- Guys and Dolls (1962, Las Vegas) — Stage success that demonstrated live performance strength.

- Hello Dolly (1967, touring) — Touring production that reaffirmed her stage value late in her career.

- Born Yesterday (1973, Jacksonville stage) — Final major acting role, a poignant capstone to decades on stage and screen.

Final Reflections

When I think about Betty Grable I see a paradox: a woman who represented an ideal while being entirely human. She was a consummate professional who endured childhood pressure, the demands of studio life, the collapse of a marriage, and a public reorientation in the face of shifting tastes. She was beloved for a persona that delivered hope to a nation during one of its most trying eras. Yet her private life reveals the familiar Hollywood pattern of personal cost behind public glamour.

Her story is a cautionary tale and a tribute. It cautions performers about the traps of being fully defined by a single marketable attribute. It honors the discipline and talent required to sustain a career across media and decades. It invites us to consider how cultural moments create icons and how those icons must navigate their own changing relevance.

Betty Grable’s image lives on in film prints, wartime memorabilia, and the biographies of Hollywood’s golden age. But beyond museum pieces and nostalgic reprints, her career teaches us about the relationship between artistry and industry, the personal sacrifices sometimes demanded by fame, and the small, quiet forms of dignity people find when the bright lights dim.

She gave audiences laughter, song, dance, and—most importantly—a respite from the world’s troubles when respite was desperately needed. For that alone she deserves to be remembered not as a faded photograph, but as a vibrant artist whose life captures both the brilliance and the sorrow of a bygone Hollywood.

0 Comments